One of the Most Savage Reprisals in History

|

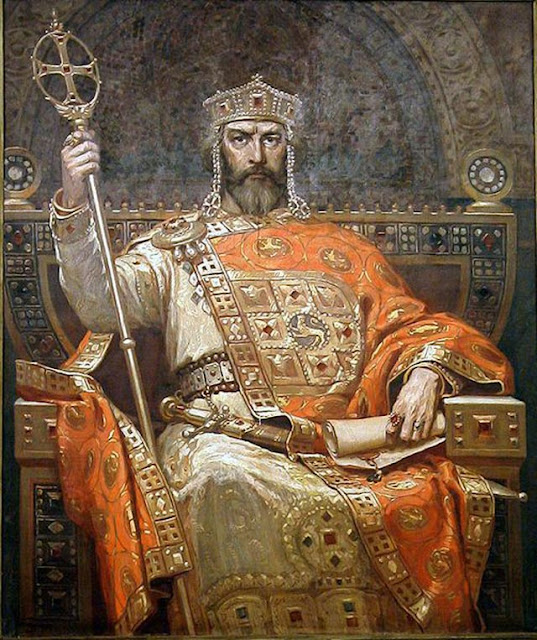

| Emperor Symeon I of Bulgaria (Sofia Cathedral). |

Byzantine history is full of memorable moments that almost seem unimaginable to modern readers. One of the oddest was the savage punishment meted out by Emperor Basil II to one of the Empire's arch-enemies, the Bulgars. The dominant historical position, adopted by scholars including Edward Gibbon, George Ostrogorsky, and John Julius Norwich, is that this incident did, in fact, occur. This view derives from the writings of contemporary historian John Skylitzes. There is a minority position held by some such as historian Mark Whittow that there isn't enough evidence to prove it actually happened. We're going with the weight of authority that Basil II earned his title "The Bulgar Slayer" from the events described below:

the blinding of 14,000 Bulgarian soldiers by Emperor Basil II in 1014 A.D.

|

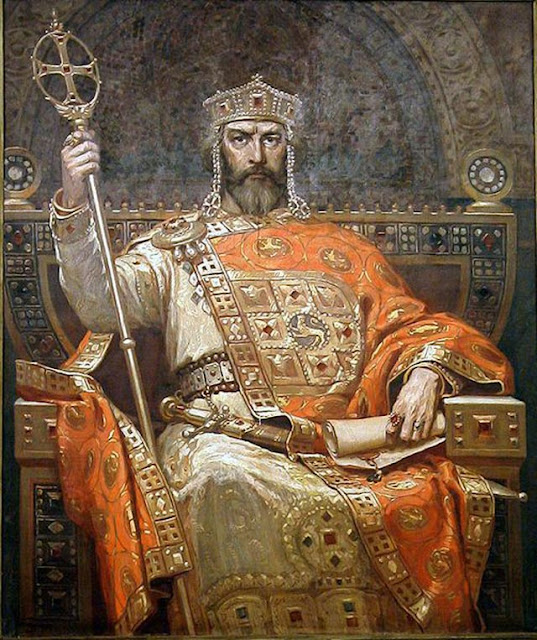

| Bulgarian Emperor Symeon I (Madrid collection via Кардам). |

Why Bulgaria Was the Byzantine Empire's Mortal Enemy For Many Years

While the Romans chose the location of Constantinople based in part on its strategic and defensible position, the Byzantine Empire acquired a variety of deadly enemies over the centuries. One of these was the Bulgarian Empire. Relations between the Byzantines and the Bulgars ebbed and flowed, but when things got hot, they got very hot indeed.

The Byzantines did a very good job of proselytizing their Christian faith to the Bulgars. However, religion caused a lot of dissension amongst the Bulgars, with many preferring the "old ways" of paganism. The first Christian ruler was Boris-Michael, who was forced to abdicate in 889, had two sons, Vladimir and Symeon. As the eldest, Vladimir succeeded Boris, but he turned out to prefer paganism. This upset the pious Boris, who had retired to a monastery. Boris came storming out of retirement, reclaimed his authority, and had Vladimir imprisoned and blinded. We're going to see that blinding is a theme in this article.

The old man didn't want to really rule anymore, so he turned things over to his younger son, Symeon (sometimes spelled Simeon) who ruled from 893-927. Symeon soon picked a quarrel with Constantinople about trade practices (Constantinople increased tariffs and removed Bulgarian merchants from the capital to Thessaloniki). Symeon promptly invaded Byzantine territory in 894 The Byzantines then pulled one of their typical crafty moves and called in the Magyars to attack Bulgaria from the rear. The Byzantines and Magyars then squeezed Bulgaria between them, Magyars in the north and Byzantines in the south. Symeon knew how to play this game, however. He concluded a truce with the Byzantines and then called in his own allies, the Patzinaks, to attack the Magyars from

their rear. After defeating the Magyars, Symeon then resumed the war against Byzantium and defeated them at Bulgarophygon in 896. The Byzantines under Leo VI sued for peace and had to pay tribute.

|

| Map of the Bulgarian Empire under Symeon at its greatest extent (credit to Todor Bozhinov). |

Things stayed quiet until a new Byzantine emperor, Alexander, decided to stop paying the tribute in 912. Symeon quickly invaded again. The Byzantine position was weakened by the fact that Alexander promptly died (913) and the rightful successor, Constantine, was only seven years old. A committee led by the Patriarch, Nicholas Mysticus, wound up running things against the bitter opposition of Alexander's widow, Zoe. All of this led to a disastrous Byzantine defeat, with the Bulgarians only stopped by Constantinople's walls. Symeon was power-mad and wanted to take over the entire Byzantine Empire and rule it himself, somewhat audacious for a Balkan ruler. The Theodosian Walls of Constantinople finally stifled this ambition, however, and he had to accept the consolation prize of being crowned Emperor of Bulgaria. He also forced the Byzantines to marry the boy Emperor, Constantine, to his daughter. This, he thought, would eventually make him the

de facto Emperor of Byzantium.

After Symeon marched back to Bulgaria, however, the Byzantines essentially repudiated the deal. Zoe used the Patriarch's concessions to Symeon to grab power from Mysticus and she forbade any marriage to some Balkan princess. Symeon was enraged and invaded Byzantine territory again, taking Adrianople in 924 and basically occupying all of the Balkan portions of Byzantium (Thrace). The new war went back and forth, with devastating Byzantine defeats at Achelous (near Anchialus) and Catasyrtae. Symeon even invaded Greece all the way down to the Gulf of Corinth. Everyone knew that Constantinople could only be captured if blockaded by both land and sea, and Symeon had no fleet. Since Empress Zoe proved to be completely incompetent, the master of the Byzantine fleet, Romanus Lecapenus, wound up as co-emperor. Symeon once again invested Constantinople in 924, but failed again. He had to content himself with the empty title of Emperor of Bulgaria, and Symeon soon was distracted by a war against the Serbs.

After Symeon's death in 927, things quieted down again. However, the Byzantines deeply resented the idea that there was another emperor in Bulgaria. The whole idea of being an emperor in the Eastern Emperor was soaked in a religious justification that the emperor was God's sole representative on earth. There really couldn't be two emperors under this reasoning - why would God need two? The idea that some minor king in the Balkans was posing as an emperor was too much for the Byzantines. However, being masterful diplomats, the Byzantines placated the Bulgarian kings by calling them emperor, but inwardly they seethed.

Things remained basically unchanged for the next sixty years. The Byzantines focused on various adventures to the south, while the Bulgarians had internal issues to deal with. Things did not change until Basil II came on the scene.

|

| Basil II the Bulgar Slayer. |

Emperor Basil II

Basil II (765-925) was one of the most capable of Byzantine Emperors. After disposing of some rivals to the throne, Basil II attacked Bulgaria. Now, Bulgaria was far from innocent, as it had been taking advantage of Byzantium's internal issues for some time. After the death of Basil II's predecessor John Tzimisces, the entire Macedonian region broke out in revolt. All of this led to the elevation of Samuel, who helped things along by killing one of his own brothers.

|

| Facial reconstruction of Emperor Samuel of Bulgaria based on his remains (courtesy Shakko). |

Samuel, like Symeon, had vast pretensions. He formed again his own Patriarchate (a previous one had been abolished by Tzimisces), a calculated affront to the Byzantines. His kingdom was based at Ochrida, which, in the grand scheme of things, was uncomfortably close to Constantinople. Samuel began raiding Byzantine territory, attacking Thessaloniki and other areas attacked by Symeon. Basically, it was the Symeon situation all over again. Everybody knew that Samuel had to be dealt with and the Bulgarians put in their place once and for all. This was up to Basil II.

However, nobody in Byzantium really thought that Basill II had it in him. Revolts broke out, and Basil II had to resort to an old Byzantine trick. He called in the Russians, specifically Prince of Kiev Vladimir, who arrived in 988 with the famous Varangian Druzina (almost always just called Varangian Guard). The Varangians like the Byzantines and Basil II and stuck around as his personal guard. They quickly dealt with the rebels, and Basil II now had a crack military and a free hand.

By this point, Basil II was sick of all the revolts and foreign states taking advantage of his empire. This made him mean and hardened. Nowadays, that may seem like a bad thing, but around 1000 A.D. that was exactly what you needed to be like in order to succeed. An emperor had to be cold and pitiless or his kingdom would not last very long and his people would become slaves. Basil II decided to pay back some of the people who had been making his life miserable, and chief among them were the Bulgarians, who were considered the Empire's most dangerous enemies anyway. And, as it turned out, he had a vivid imagination as to how to do that.

So, Basil II set about not just defeating the Bulgarians, but eliminating them. They had made his accession to the throne miserable and their leader fancied himself his equal. The Byzantines had had enough. It was high time to swat down these insolent upstarts and return things to the way they ought to be - with the Emperor of Constantinople the only emperor and master of God's kingdom on earth. Basil II, it turned out, was the right man for the job.

The takeaway from all this is that Basil II both personally and as a patriot deeply resented the Bulgars and was determined to end their threat permanently. What followed was a devastating war of annihilation which went back and forth at times, but with the Byzantines generally gaining the upper hand. The war was constant, with no breaks for winter as was customary at the time, perhaps the first time in history this was done. Anyone who doubts the quality of the Byzantine military can study these campaigns in detail to reorient their thinking in the proper direction.

|

| The blinding of Samuel's army and their return to Prilep. |

The Blinding of the Bulgarian Army

This has been a lengthy and involved leadup to the topic of this article, but it was necessary. It is important to understand the depth of hate and resentment felt by the Byzantines in general and Basil II in particular toward the Bulgars to appreciate what happened next.

As Basil II made inroads on Samuel's kingdom, Samuel's supporters started to become scarce. Basil II recovered long-lost Byzantine possessions such as Dyrrachium on the Adriatic and gradually squeezed the Bulgars into a mountain stronghold. In July 1014, Basil II surrounded Samuel's remaining army in the Belasica mounts (the Battle of Kleidion) near the upper Struma River. The army was captured largely intact in a valley. Samuel escaped to Prilep, but the Bulgarian army did not. There were about 14,000 or 15,000 Bulgarian survivors - accounts differ. Having defeated the Bulgars, Basil II now adopted the title Bulgaroctonus, or Bulgar-Slayer. However, what he did next is what went down into history.

Basil II ordered that the captured Bulgars be blinded and then put into groups of one hundred men each. Each of these groups was given a single one-eyed man as a guide and sent back to Prilep to see Samuel. According to the historical accounts, when Samuel saw the blinded men approaching, he had a stroke or similar ailment and died two days later (6 October 914).

A natural question is why Basil II blinded the soldiers and didn't just make them slaves or even recruit them into Imperial service. Of course, that depends on what he was thinking, and we will never know that. There are various theories. One is that Basil II was retaliating for the loss of one of his favorite generals, Theophylact Botaneiates, and his son in an ambush right after the victory at the Battle of Kleidion. The circumstances of Botaneiates' death were murky, but one account said that Samuel's own son ran him through with a spear. Another theory is that blinding was just a typical punishment of the times according to this theory. However, while some barbaric punishments including the cutting off of noses were in fashion at the time, blinding was not generally carried out on prisoners except in rare cases where royalty was involved.

My own view is that Basil II decided that he wanted to send a very clear and unmistakable message to Samuel, and Western Union wasn't available.

|

| The real star of our story is not Emperor Basil II, Symeon, nor Samuel. It is the walls of Constantinople, which humbled the most powerful people in the world for a thousand years. |

Conclusion

Due to the events described in this article, Basil II is a very controversial figure among students of history. He is not particularly beloved in Bulgaria and other Balkan nations. There are some who simply don't like what Basil II did and try to find creative ways to demean him or deny what he did entirely. You might think that the politics of events disappear after a thousand years, but they don't. That is just how things work when there isn't video or photographic proof and few reliable written sources. But, as noted above, this article takes the mainstream position that Basil II did defeat the Bulgars, blind its captured soldiers, and thereby end the Bulgarian Empire.

Basil II virtually ended the Bulgars as a threat to his kingdom. It was one of the decisive defeats of the Middle Ages, completely wiping out what had been considered the main threat to the Byzantine state. The Bulgarian Empire ceased to exist within a few years, and Basil II treated the conquered people magnanimously. All of this cemented his victory. Never again did the Bulgars threaten Constantinople. Instead, they became just another minor player in the Balkans. However, they did retain their Patriarch and continued their acceptance of Eastern Orthodoxy as their enduring religion.

2021