Justinian vs. Basil II, Head to Head

|

| Roman Emperor Constantine the Great presents his city, Constantinople, to God as depicted in a mosaic at Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey. |

There were 94 Byzantine Emperors, beginning with Constantine the Great (324-337 A.D.) and ending with Constantine XI (1449-1453). This number includes Empresses. There were nine times when co-Emperors served at the same time, though five of these instances involved one Empress, Zoe, who never served alone.

While Byzantium had quite a few bad and ineffectual emperors, it also had its share of brilliant and capable leaders. Generally, those two qualities go hand-in-hand, but that's not always the case with emperors. One can have grand plans but be ineffectual or misguided in trying to realize them. On the other hand, having modest and realistic aims but fulfilling them brilliantly makes for a superb emperor.

Constantine the Great was more of a Roman Emperor than a Byzantine one. Although he earned the sobriquet "Great," Constantine was only technically a Byzantine emperor. Constantine belongs in a separate category and needs to be compared with his peers such as Trajan and Augustus who ruled over the full Roman Empire, not with emperors that ruled only over the Eastern Roman Empire. The latter had vastly fewer resources and different issues to resolve than Roman Emperors.

Emperor Theodosius split the Roman Empire between his two sons, and that is when fair comparisons begin. Thus, only the Eastern Roman - or Byzantine - emperors following Theodosius are considered here.

As to why I call the Eastern Roman Empire "Byzantine," I've explained the derivation of that word elsewhere. Suffice to say here that it is primarily to avoid confusion and the intent is not to inflame anyone who is dead set on calling Byzantium The Eastern Roman Empire out of sentimentality or because that's what their old Latin teacher called it.

Speaking of Latin teachers, unless you've read up on Byzantium, the only Byzantine emperor they probably ever mentioned to you was Justinian (527-565 A.D.). Justinian is perhaps the only Byzantine emperor who ascends to true celebrity status, still a household name like "Cher" or "Elton." It's not exaggerating much to say that many people probably think that Justinian was the only Byzantine emperor.

Well, Justinian (who also gets called "the Great," but not as often as Constantine) deserves the respect he gets. He oversaw a lot of phenomenal things, some of which still matter today (such as the construction of the Haghia Sophia church in Constantinople/ Istanbul). If this were a contest of celebrity, Justinian is the clear winner, even likely beating Constantine.

But it's not. We're going to go through several categories and test Justinian's actual accomplishments and legacy against the challenger I have selected: Basil II (976-1025 A.D.). Students of Byzantium should be nodding their heads at this point, as Basil II of the Macedonian Dynasty is the only medieval Byzantine emperor who ascends above the clutter of background noise to achieve some celebrity of his own. I'm not even going to discuss any other possible challengers here because I believe this pair of emperors stands head and shoulders above the rest.

While you may not recognize the name Basil II because you're not a Byzantine scholar, you almost certainly have heard of something he did that has echoed down the ages. Once you realize he's the one that did it, you'll hopefully nod your head in recognition that this was an important emperor. We'll get to that below.

Without further ado, let's get on with it.

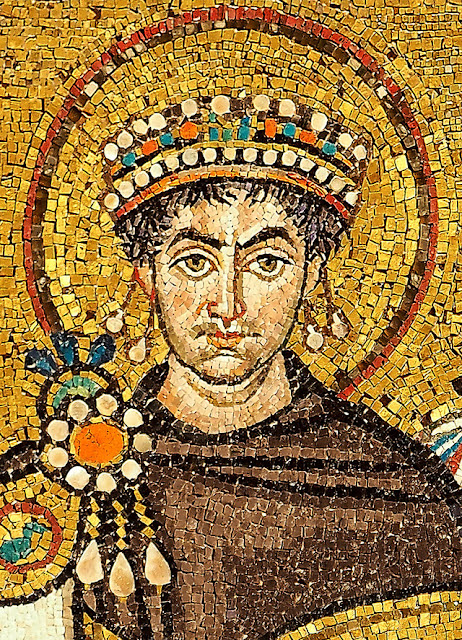

|

| Emperor Justinian in the only known depiction of him from his lifetime, in an Italian church. |

Justinian and Basil II Origins: Tie

You may not think that how an emperor ascended to the throne is significant, but legitimacy matters. There were emperors who personally killed their predecessors, and this left a stain over their entire reign. On the other hand, there were emperors who earned their way onto the throne through military valor and similar deeds.

The people of Constantinople paid close attention to matters like this. It was a very gossipy city. In many ways, it was like Rome during the bread-and-circuses days. An emperor who had Constantinople's masses behind him eliminated a large source of problems and generally had a better chance of ruling successfully.

Justinian was made co-emperor by Emperor Justin, an old man by the end of his reign, on 1 April 527. This was only a few months before Justin died, leaving Justinian as the sole emperor. Justinian apparently was the son of Justin's sister. Justin had sent for him from his native lands in latter-day Yugoslavia and groomed him to become a leader. Justin and Justinian got on well, and there is a suspicion that Justinian served as Justin's de facto regent during the last years of his life.

Under Byzantine precedent and custom, this means Justinian was a legitimate emperor even though he wasn't "born in the purple."

Basil II, however, was "born into the purple" to Emperor Romanos II. His father made Basil II co-emperor in 960, though he was only about two years old then. As the eldest son, Basil II was a natural successor, though things didn't necessarily work that way in Byzantium. His younger brother (and eventual successor), Constantine VIII, similarly was crowned a couple of years later.

While various palace intrigues typical of Byzantium then followed, Basil II had clear legitimacy when John I (John Tzimisces) died on 10 January 976 (a general, Nikephoros Phokas, had staged a coup and then tried to legitimize it by marrying Basil II's mother Theophano, but she and Tzimisces murdered Phokas before Tzimisces conveniently died).

So, since both Justinian and Basil II were legitimate emperors, this category is a tie with perhaps a very marginal edge to Basil II.

|

| Emperor Basil II. |

Basil II and Justinian Popularity: Edge to Basil II

An emperor's popularity was vitally important in Byzantium. There were cases when an emperor literally was attacked in the street by a mob and lost the throne. Legitimacy was one reason an emperor could become unpopular, but there were many others.

Justinian, despite his later fame, was not particularly popular with the citizens of Constantinople. He closely associated himself with the "Blues," one of two political parties apparently deriving from chariot races. This automatically meant that he was not as popular with the other political party, the "Greens."

Due to Justinian's imperial connections and his association with them, the Blues enjoyed a certain immunity from reprisal by city authorities. The Greens, meanwhile, were repressed and couldn't get away with anything. This rubbed a lot of people the wrong way, in particular Justinian's real-time biographer Procopius. The "Secret History" of Procopius has a lot to say about Justinian, and none of it is good.

However, bad as the things Procopius wrote about Justinian were, they paled in comparison to the portrait painted of Justinian's wife, Theodora. Procopius' allegations about her are some of the most savage in all of biographical history. Think of the worst things that you could possibly say about any woman, and that's what Procopius wrote about Theodora.

Obviously, there was a market for what Procopius wrote. He undoubtedly was not the only one to think ill of the emperor. Things came to a head in January 532, when the Greens gathered in the Hippodrome and began loudly expressing their dislike for Justinian and everything associated with him. This led to a gradual escalation of violence in subsequent days.

Justinian's support among the Blues then unexpectedly collapsed. Apparently, there was resentment on both sides about some crackdowns the government had been imposing. Everybody began chanting "Nika" ("win") together and a huge riot broke out that lasted for days.

Justinian, with help from Theodora and some sympathetic generals, eventually suppressed the very dangerous Nika Riot. However, it is fair to say that he was never particularly liked by the populace, and this situation did not show much improvement over time,

Basil II, on the other hand, was fairly popular. He lowered taxes for country farmers and followed the popular (and politically wise) strategy of reducing the privileges and wealth of large landowners. Among other measures, he instituted a special tax (the allelengyon tax) to be paid by the large landowners. In effect, Basil II made the rich "pay their fair share" as the current saying goes. This proved quite popular with the masses and also quite beneficial to the treasury, though the aristocracy bided its time and got Basil II's successor to reverse many of these changes.

In terms of popularity, Basil II is the clear winner over Justinian.

|

| A Byzantine tax collector at work. |

Basil II and Justinian's Fiscal Policy: Edge to Basil II

Fiscal policy may seem like a tedious subject. It certainly is not as gripping as reading about military battles where someone wins and someone else has his head cut off. But Byzantine fiscal policy was of tremendous importance to the fate of the empire. In fact, there are theories that suggest Muslim advances were actually encouraged by many landowners who hated paying high taxes every year.

Justinian found just the man he needed to be his tax collector. He plucked John of Cappodocia out of obscurity and installed him as Praetorian Prefect. While this may sound like a military position, it actually encompassed a much wider scope that included tax collections. In essence, John of Cappodocia became the head of the Byzantine IRS. He was famous for being incorruptible and also was quite brutal in his methods.

John was hated by just about everyone. The Nika rioters demanded his dismissal, and Justinian complied - only to quietly rehire him a few months later. By 540, Antonina, the wife of the great general Belisarius, had had quite enough of John. She set him up by inducing him to attend a meeting at which a treasonous plot to replace Justinian with Belisarius was discussed - and then arranged to have the authorities arrest everyone who was there. This led eventually to John's downfall at the insistence of Theodora, who also hated him.

While it is standard practice for those discussing Justinian to point to the map of his conquests, the Byzantine public never saw such maps during Justinian's lifetime. All they saw were grinding campaigns that seemed to be leading nowhere, endless expeditions to this or that far-flung place, and onerous taxes. A lot of the tax money collected was given to northern enemies as bribes to keep them quiet while Belisarius won victories in remote areas that did not affect daily life. It is no wonder that Justinian was unpopular, the wonder is that he managed to remain in power at all.

Byzantine taxes during Justinian's reign were calculated in a "top-down" fashion. This means that government expenses for the year were calculated, and then taxes were set accordingly. Justinian's government never had to "live within its means." Instead, whatever crazy project he decided to embark upon, the people had to fund regardless of a good or bad harvest. This "top-down" system did not disappear until the middle of the 7th Century with the adoption of the Themes.

Justinian also economized at the expense of civilians. For instance, he restricted the public Post, reduced government pensions, curtailed public amusements, and reduced the distribution of corn. Basically, Justinian taxed people heavily and took away their bread and circuses.

This is not to say that Justinian wasted all of his taxes. In fact, he financed some of the marvels of all time, such as the Haghia Sophia church in Constantinople that remains the greatest architectural achievement of antiquity. However, the money went out as fast as it came in, and a lack of funds prevented his successors from building upon or even preserving many of his achievements.

Basil II did not share Justinian's grand military plans. As noted above, he raised funds in ways that were popular with the masses. Among his other innovations was a treaty with Venice reducing their tariffs in exchange for the transport of Byzantine troops to southern Italy. Because of such shrewd tactics, there were adequate funds left in the treasury for an expedition to recover Sicily that did not take place until after his death. All of this Basil II accomplished despite his forces, like Justinian's, also being in a state of almost constant war.

In terms of fiscal policies, Basil II is the clear winner.

|

| Justinian's Basilica Cistern in Istanbul. |

Basil II and Justinian Cultural Success: Edge to Justinian

Justinian is known for the map of his conquests, but that actually wasn't his greatest achievement. Instead, he - or rather, his administration - created cultural achievements that endure to today.

Justinian's most obvious cultural success was the construction of the remarkable Haghia Sophia church. Designed by Anthemius of Tralles, the dome of the church had no precedent in ancient architecture and required remarkable mathematical skill (the dome later collapsed and had to be rebuilt by Isidore of Militus, and that dome is the one that still stands today). Anthemius also experimented with solar power, concentrating the sun's rays using mirrors for military purposes.

Another innovation that helped assure Constantinople was Justinian's construction of the Basilica Cistern. This can still be visited today. Justinian also funded massive fortifications in vulnerable spots along the border and bridges where necessary.

Justinian's legacy was not just in bricks and mortar. He oversaw a rewriting of Roman law to make it applicable to contemporary situations. This Corpus Juris Civilis formed the basis of modern law in many places. Quaestor of the Sacred Palaces Tribonian oversaw this process and also the drafting of legislation (the Novels) that characterized the first half of Justinian's reign.

Basil II had nothing to compare with Justinian's great cultural achievements. He was a warrior who left his mark on the battlefield. There is no question that Justinian is the clear winner over Basil II in the area of cultural advancement.

|

| The extent of Justinian's conquests. |

Justinian and Basil II Military Success: Tie

The first thing that everyone learns about Justinian is that he recovered vast lands once held but lost by the Roman Empire. His plan was simple in concept but breathtaking in scope: renovatio imperii, or "restoration of the Empire" An old dream of any Roman patriot, it reflected Justinian's backward glance to the glories that once were rather than a truly forward look to the realities and possibilities of the future.This was Justinian's main claim to fame for posterity, and it is a good one because of the degree of success he had. A look at the map of Justinian's conquests shows an extraordinary recovery of lost land in Italy, North Africa, and elsewhere.

2021

However, military success is only worthwhile if it is useful to some larger purpose. Justinian's campaigns led by Belisarius and other brilliant generals including Narses and Sittas were flashy successes to posterity but only minimally worthwhile in the long run. In a nutshell, they overextended the Byzantine Empire.

For instance, Justinian conquered Italy. There is no question at all about this, and the Byzantine Empire never again possessed the entire Italian peninsula. This was an epic achievement.

|

| The Byzantine Empire ca. 600 A.D. (purple, at right), showing the loss of most of Italy and other Justinian conquests by the end of the Sixth Century. |

Unfortunately, though, the conquest of Italy meant very little for the future of the empire. Most of the gains in Italy were soon reversed. While the Byzantine Empire did hold outposts in Italy until the 12th Century, they did little for the health of the empire. The Italian possessions required constant expenditures of time, money, and effort for little or no return. They eventually served as little more than a lightning rod for Western adventurers to attack Byzantium.

Basil II has never received the military acclaim that Justinian did. However, in some ways, his military successes were more meaningful. His orientation was not to the west, like Justinian, but to the north and east. There, he had brilliant successes and extended the borders of the empire to their greatest territorial extent since the Muslim conquests four centuries earlier.

Basil II has never received the military acclaim that Justinian did. However, in some ways, his military successes were more meaningful. His orientation was not to the west, like Justinian, but to the north and east. There, he had brilliant successes and extended the borders of the empire to their greatest territorial extent since the Muslim conquests four centuries earlier.

The main difference between the two Emperors was in their style of leadership. Justinian remained in his palace on the Bosphorus (for the most part) and acted as a string-puller. This may sound weak, but Justinian had some of the best strings to pull in all of history, and that is to his credit. Belisarius, Narses, and his other generals were the best generals of the entire Middle Ages.

Justinian was right to just leave the fighting to the Belisarius and the others, supporting them adequately as necessary. His methods worked, and whether they made him look "heroic" or not is irrelevant. As a military amateur in the presence of truly great military leaders, Justinian was right to not insert himself into campaigns which he could only mess up while risking his own life. As a successful grand strategist, Justinian has had few peers.

Basil II's leadership style was 180 degrees opposite to Justinian's style. He personally led campaigns, marched with the troops, and was there, on the spot, to make instant decisions. We could say that Basil II "led from the front," though there weren't "fronts" then in the 20th Century sense.

At times, this made a huge difference in outcomes. Basil II riding his horse through storms and icy cold conditions to achieve his ends may sound leaps and bounds better than Justinian's style, but both were successful in their own ways. We can admire the picture of Basil II eating with the troops, riding his horse down dusty roads with them, and risking his life with the men, but the important thing is not the image (which the general populace wouldn't have known much about anyway due to the media realities of the time). Instead, it is results and nothing but results.

If Basil II had to lead from the front, it's also an indication that he didn't develop truly great generals like Justinian. You may say, well, that was just the hand he was dealt, and there is truth in that. However, Basil II also had issues with finding quality people in other areas, most notably in grooming a successor. Michael Bourtzes is a case in point. A reasonably competent general, he had some successes but ultimately failed and had highly questionable ethics. The bottom line is that Basil II was a dynamic leader who was forced to risk his life in campaigns because he was unable - for whatever reasons, which, yes, may have been outside of his control - to develop a good "bench." That is not necessarily a failing of Basil II but puts Justinian in a better light because he did develop and support talent.

Again, there's no reason to hold the low quality of supporting players against Basil II. His results are what matter, and those results in the military arena were outstanding. That is what we are comparing here, results.

As an illustration of Basil II's leadership style making a difference, perhaps his greatest military achievement was saving Aleppo in the winter of 994-995. Manju Takin (Manjutakin), a Fatimid slave-general under al-Aziz, was besieging the city, and Basil was on one of his expeditions into Bulgaria. Knowing that speed was of the essence, Basil had his entire army mounted on horses and mules and force-marched down to Syria. This was accomplished in a month, an incredibly short time for the era. Basil II then completely restored the situation in the East, with a few minor exceptions such as not retaking Tripolis.

However, reversing the losses in the east was far from Basil II's greatest achievement. He earned the title "Bulgar Slayer" by finally, once and for all, ending the persistent threat from the north that had plagued the empire for centuries. Once and for all, he decapitated the medieval Bulgar empire, which never again posed a serious threat to Byzantine power. He also formed the famous Varangian Guard that served as the emperor's bodyguards for the next several hundred years.

To this point, I've painted a picture where Justinian dangerously overstretched his empire, leading to quick losses, while Basil II was all-conquering and shrewd. Most historians stop there and crown Basil II the better commander.

Not so fast. Basil II also overstretched Byzantine territory. However, unlike Justiniana, he did it to the east. Byzantium simply did not have the resources to defend lands east of Lake Van. The attempt to do so less than 50 years after Basil II's passing led to the catastrophic Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

This Byzantine defeat led to the permanent and irrevocable loss of even more important territory than the losses following Justinian's reign. That is because Anatolia formed the very heart of Byzantine power and resources, while Italy, Spain, and North Africa - lost after Justinian's passing - were almost irrelevant to Byzantine survival.

When we look at Justinian and Basil II, we see they made the same fatal mistake: overstretch. Imperial overstretch led to the loss of many of their gains before the end of their respective centuries. Extremely hard work saved the situation both times, but the lands lost were never recovered. It is said that victory sows the seeds of its own defeat, and Byzantine history in the ages of Justinian and Basil II are eerily similar in proving that point. The subsequent territorial losses weren't their fault, but Justinian and Basil II set the table for them.

That is why this category is a tie.

Oh, yes, I mentioned above that even if you don't know anything about Byzantine history that you've heard of something that Basil II did. Many people have heard the medieval legend of the columns of blind men marching down the road with their hands on each other's shoulders for guidance, with only a few men left with one eye to lead them. Many people probably think it's just a "moral lesson" or something like that with no basis in reality.

That's not a legend. Basil II did that to the Bulgar army after their final defeat. He sent about 15,000 enemy soldiers back to their kingdom blinded. One man was left with one eye per 100 men as a guide. You've probably heard of the phrases "the blind leading the blind" and "in the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king." Well, you can thank Basil II indirectly for those sayings.

It caused the Bulgar leader to have a stroke and die when he saw them. That basically ended the medieval Bulgar kingdom. It was one of the most notorious incidents in all of military history, and it succeeded completely in ending the wars between the two powers.

|

| The Byzantine Empire after the reign of Basil II. |

Conclusion

I have methodically compared the Byzantine Emperors Justinian and Basil II using a variety of easily understood criteria. While other categories could be used, such as their impact on religion (extremely important in Byzantium) and their succession (neither man had any success with that), these categories reflect the clearest similarities and differences between the two men.

Overall, Basil II scores higher in several categories such as fiscal policy and popularity. I personally feel that Basil II was the greatest Byzantine Emperor because he left the empire on a sounder footing when he left than when he found it (though his incompetent successors squandered this gift in a record time). Justinian did not. Those are hard but inescapable truths.

But Basil II's win is not completely clear-cut. Justinian clearly wins in cultural achievement, and that is by a wide margin. Constructing enduring monuments such as the Haghia Sophia and regenerating Roman law had more impact on the world than winning some battles, Justinian left gifts to posterity that still echo today. These lasting gifts are why he is remembered by ordinary people while Basil II is forgotten except by historians. In terms of their overall effect on the future of the empire, Basil II did a slightly better job, but both emperors achieved some of the greatest successes of the middle ages.

|

| Territory added by Basil II to the Byzantine Empire is shown in yellow. |

2021