The Roman Empire Was Doomed

|

| "The Fall of Rome." Thomas Cole (February 1, 1801 – February 11, 1848). |

Why did the Roman Empire fall?

The Roman Empire lasted for about 1500 years and, if you count the beginning of the Roman culture from Rome's founding, about 2000 years. There is a wealth of information, first-hand accounts, and histories of the Empire. However, despite this, the causes for the Roman Empire's ultimate collapse remain controversial.

I believe there are five obvious reasons why the Roman Empire could not last. While I could write for days on this topic, I am going to spare you and only write briefly on each contributing factor.

This article will take an unusual approach compared to almost every other historian that approaches the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Instead of focusing just on the classical Empire, the one with Trajan and Nero and Marcus Aurelius and so on, here we also are going to look at similarities with the Byzantine Empire that lasted for another thousand years. The Eastern Roman Empire had the same flaws and vulnerabilities as the classical empire and perished for eerily similar reasons.

While the Roman system changed substantially between the time of the founding of the Republic and then on to Augustus and the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the same core factors contributed to its ultimate failure regardless of which epoch you choose to focus on. The system did evolve, but the underlying authoritarian ethos remained intact all the way through, like a historic house that just gets a new coat of paint or aluminum siding.

I am going to list my five reasons for the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in no particular order because they all intertwined and contributed to each other. There are just capsule summaries with minimal examples because I am not trying to prove anything here. Nobody is ever going to prove anything regarding the decline of the Roman system, there are just too many factors, theories, and opinions. Instead, I am trying to make this as readable and enjoyable as I can.

I could give you ten more different examples for each point, though.

Edward Gibbon (The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,) spent his life on this topic and today his main theory - that the Roman civilization fell due to growing decadence - is largely ignored or derided. However, Gibbon's theory has a germ of truth, though not in the moralistic way he apparently meant. I will get to that below. But the main point is that simply spending time and writing endlessly on this is not the answer. You can have ten citations on every page like Gibbon and still not solve this. The causes are too complex and conclusions shift according to the writer's own judgments (Gibbon had very definite ideas about religion and morality and a parochial attitude based on his allegiance to the British Empire). There is no "answer," there are only lessons to answer questions that you, the reader, have facing today's world.

There should be just enough in this article, though, to make you think about this topic from a new perspective and help you to draw your own conclusions. Life is for the living, the future is what matters.

|

| Hannibal Barca of Carthage. Rome found it easier to defeat Carthage than endless bands of migrants coming across its borders at random (marble bust found at the ancient city-state of Capua in Italy). |

The Types of Rome's Enemies Changed To The Empire's Disadvantage

When you look at the history of Rome's conquest of the Mediterranean basin and then later areas somewhat removed from it, certain things stand out. Competing civilizations at that time were based on the same basic model of a central government, associated cities, heavy taxation to fund large armies or armies of virtual slaves, and integrated economic systems. The "barbarian nations" of 200 B.C. were vastly different than those of 700 A.D.

Rome's major early adversaries all featured this pattern. Rome's first large-scale opponent for control of the Mediterranean was Carthage. Yes, it was a hard-fought series of wars, but once Hannibal Barca was defeated for the final time at the Battle of Zama, resistance was over. Roman soldiers destroyed the capital city and salted its fields and that was that. Roman control of the Mediterranean was never again seriously challenged. The same pattern asserted itself in Egypt, Greece, and Gaul. Fight the enemy's main armies, defeat them, and after that live happily ever after.

The same pattern held true for the Byzantines. Heraclius could defeat the Sassanids, Basil II the Bulgars, and these ended specific threats. However, ultimately the Byzantines ran into essentially nationless crusading barons from the West and hordes of loosely amalgamated Arab tribes from the East that swarmed the frontier. No matter how many of these attackers the Byzantines defeated, they were constantly replaced by others of a similar mindset. Capture one city and another enemy sprang up somewhere else. There was no Carthage to conquer and end matters once and for all.

Society in the Roman Empire and its remnants also was changing. Rome was an empire of cities. Over time, for various reasons, cities went into decline. For a society that revolved around cities connected by limitless roads, this was cataclysmic. Rome's enemies were far ahead in this trend, largely eschewing cities that Rome could conquer and thereby end their threats. If the Roman legions subdued one barbarian village, there were a hundred others of roughly equal size left.

The nature of Rome's enemies thus changed as time went by. They increased in number and changed in form. Adversaries stopped being far-flung empires where you could capture the capital, defeat the king, and end all resistance or impose an enforceable peace and demand tribute. Formal armies turned into roving bands of nomads and wanderers, forest people who had no obvious capital and really not even a form of government aside from tribal leaders. A band of them would cross a river here, another band there, and do whatever damage they could. The Roman defenses could not police every square inch of the frontier and thus breakthroughs became endemic. The invaders of 450 A.D. more resembled the partisan of 1943 than the Carthaginian armies of elephants of 200 B.C.

The result was endless warfare. Frontier battles never ended and drained wealth and manpower. Search and destroy missions into Germania or the Balkans never erased threats, only temporarily minimized them. The Roman frontier became like a basket full of water that had numerous leaks. No matter how many holes they plugged up, there were others elsewhere growing larger.

The Roman Economy Collapsed

Economic collapse of the Roman economy is a favorite of historians because it has a lot of merit and some proof based on historical records. The most obvious data historians point to is inflation, which took off during the Third Century. However, in my view, Roman inflation was the result of other underlying factors. Inflation was a symptom, not a cause.

When you write "economic collapse" it comes across as a sudden thing, like a house that suddenly explodes. Rome's economic collapse in both the Eastern and Western Empires was a slow, grinding, gradual process that lasted for centuries in each case. There were insidious factors that were never corrected because they were not recognized as problems - in fact, in some cases (like Byzantium's treaties with Venice and Genoa), they were actually seen as positives (as the situation deteriorated, any contact with the powerful western nations as prized even though they were strangling the Empire by cutting off the Empire's revenue and vigor). The Roman Empire's economic collapse was not like a balloon being punctured with a pin. Instead, it was more like a slow leak where the balloon is tied together that is invisible but inexorable.

The early (and most successful) Roman economy was built on slavery. This is not something anyone wants to hear today, because slavery is bad and nobody wants to say anything positive about it in any way, shape, or form. But slavery was the boon and then curse of the Roman economy.

Slavery is an inefficient economic system. Much better is freedom and positive incentive, which brings innovation, entrepreneurship, and satisfaction. However, as an expansionary power, Rome secured a steady supply of slaves by defeating rivals and this sustained its early growth.

Why Rome was able to expand in its early days is a completely separate topic, but let me address it briefly. Essentially, Rome was in a favorable location where it could defeat smaller adversaries, and the adversaries only gradually became bigger over time. As each small enemy was defeated, it provided a supply of slaves who could build weapons and fortifications and ships that would enable Rome to defeat the next, slightly larger, adversary. This has some similarities to the Third Reich's conquest of smaller nations in 1939-1941 that gave it economic power and enabled it to finally take on the big dogs of the USSR and the USA.

There is a fundamental problem with this growth model. What happens when you run out of new slaves from conquests? Rome found out the answer to this the hard way when it stopped expanding and stopped getting new supplies of slaves. The answer is economic stagnation. In Rome's case, the decline did not set in immediately after Emperor Trajan took the empire to its greatest extent ca. 117 A.D. The economy was good enough to keep things going for a long time after that. However, by the Third Century a hundred years later, the economic stagnation due to the lack of new conquests to feed the slavery machine was in full swing. That also happens to be when Roman inflation skyrocketed.

The cause of Byzantium's economic decline is slightly different but arose from the same fundamental problems of relying on others to do the dirty work. While never a particularly expansionary power, Byzantium relied heavily on trade and certain key industries (such as agriculture in Egypt, silkworms, agriculture, and customs dues from trade) for its income.

Well, Egypt was lost early on during the Arab invasions and silkworms alone could not take up the slack. Byzantium was never a big exporter of agriculture, most of its production being needed for internal needs and the endless civil wars continually laying waste to valuable cropland. That leaves customs dues, which actually provided a pretty good revenue stream. However, it, too, eventually dried up, and here is where we see the beginning of the true decline of the Byzantine state.

We even have a specific villain: Venice, and to a much lesser extent Genoa. The first economic treaty between Constantinople and Venice was made in 1082 by Emperor Alexius I Komnenos. He had his reasons, and they were good ones. Alexius covered current needs (a feared invasion from the West) by enlisting a powerful Western ally. This economic alliance worked out fairly well, at least at first. Venice became virtually an economic partner to Byzantium, supplying ships in exchange for reduced customs dues and other special privileges (eventually, Venetians weren't even subject to Byzantine law any longer).

Alexius had no way of knowing these agreements would become the cancer eating away at the soul of his kingdom. The whole mindset of the Byzantines, however, was that what was established in the past was the best way. So, as time went on, the increasingly onerous treaties with Venice were seen almost as obligatory and part of the national identity, like calling themselves Romans.

We all know how that turned out. The Venetians got a taste of Byzantine wealth derived from trade revenues and decided they'd like to have all that income for themselves. This led to the Fourth Crusade, in which crass Venetian leaders cleverly manipulated a Crusade begun with high-minded initial motives into a vulgar and unprovoked invasion of Byzantium.

Byzantium ultimately recovered to one extent or another from the Fourth Crusade, but its leaders did not learn their lessons. Incredible as it may seem, the Byzantine Emperors quickly returned to the practice of disadvantageous trade treaties with Venice, the very invader that had almost destroyed the Empire in 1204. These treaties sapped the Empire of absolutely critical revenue and led to the collapse of the Byzantine navy and merchant fleet. Why build ships when the Venetians were taking care of that now? This accelerated the economic stagnation mentioned above in multiple ways. Much as the car industry generated huge swathes of employment in the US economy of the 1950s, the shipping industry had powered a large part of the Byzantine economy. Now, it was basically gone.

By the time of Andronicus II ca. 1300, the process of essentially paying Venice to take care of all shipping needs was irreversible. It led to the increasing impoverishment of the Empire. By the mid-1300s, the Imperial Court was reduced to eating off of wooden plates. An empress hocked the crown jewels to - you guessed it - Venice. The Venetians almost defeated the Empire in 1204, but they finally did destroy it through one-sided trade agreements.

Economic collapse is the saddest way for an empire to disintegrate, but it is a common feature of history. Just look at Spain in the 1700s or the Ottoman Empire in the 1800s. While the specific causes were unique to the classical Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire, the process of destruction from within was the same.

|

| Migrations from the East were continuous and unstoppable, both during the classical Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire (Modified from World History: Ancient Civilizations, 2006, pp. 503). |

Migratory Patterns Were Unstoppable

All students of Rome are familiar with the frontier fortresses along major rivers (Rhine and Danube primarily) and in Anatolia that ultimately failed. Their failure, however, was only symptomatic of the larger cause: unstoppable migratory patterns out of Asia. This vulnerability was common to both the classical Empire and the Byzantine Empire. Really, the only difference was who was invading.

These migrations are known quaintly as the "barbarian invasions." It is a term favored by the Romans themselves. It makes the process sound as though a bunch of cavemen just suddenly decided to head west for no particular reason aside from plunder and conquest. The more modern term is "the migration period," which is a more accurate description.

The most famous of these migratory invasions in the classical period was by Attila the Hun, who ultimately was at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plans but caused immense damage. The later Ottoman invasion that led to the defining endpoint to the process in 1453 also is well known. Attila and the Ottomans were simply part of a larger movement from east to west that began roughly in 300 A.D. and pretty much ended, strangely enough, around the time of the fall of Constantinople in 1453 (the Ottomans kept trying to expand west for another 200 years, but failed). The Roman Empire - both classical and medieval - was supremely unlucky to face this endless threat throughout its existence.

Was this migration just a bunch of predatory tribes bent on looting Roman civilization? Absolutely not. The process was too sustained and too painful for it to have been generated solely by predatory instincts for lands and booty (though, at times, that surely was a motivation for certain invaders). It was a movement of people for far larger reasons than mere avarice.

Almost everything about these migratory patterns is debatable aside from their effect, but that is clear-cut. They overwhelmed the Roman and Byzantine defenses like a flood breaking through a levee. Whether the migration was due to disease or oppression in the east or whether the decline of the Roman Empire was an independent factor that actually spurred on the migration is ripe for discussion.

My own view is that a changing climate was a key culprit in these migratory waves. The benign Mediterranean climate of the Republic and early Empire gradually got colder and less moist. The climatic changes culminated in the "Late Antique Little Ice Age," spurred on by various volcanic eruptions. This climate change brought about plagues (the Antonine Plague marked the high point and beginning of the decline of Roman civilization, the Plague of Cyprian in the Third Century accelerated the decline, and the Bubonic Plague in the Sixth Century eliminated the final attempt by Justinian to put the broken Empire back together again. In Byzantium, the Black Death of the 14th Century (said to have arrived in Constantinople on a ship of dying men) was really the final nail in the coffin of the struggling Byzantine Empire.

If you believe that climate change is too abstract and gradual to account for the collapse of a mighty civilization, a similar process appears to have destroyed the Sumerian civilization. Their crops failed, wheat fields had to be replaced with less useful barley, and eventually, their cities became uninhabitable. Cities once on the coast and with farmland all around are now in the middle of barren deserts. This made the Sumerians vulnerable to attacks from the "barbarian" hill people to the north. The sequence was slightly different ("history does not repeat, it rhymes") but the outcome was an even more total collapse. The Romans and Byzantines actually held on fairly well in comparison.

The thing about the climate is that it is always changing. Always has and always will. Humans either adapt or their societies vanish.

While Rome and Byzantium rebounded from these successive disasters, they had a cumulatively destructive effect. The rebounds were successively weaker and diminished by rampant unhappiness that led to coup attempts and disunity. The change was most pronounced and had the most effect on Roman civilization in the northern areas of the Empire such as Gaul and Latin Britannia. For instance, Roman crops did worse as time went on and Roman villas became less comfortable. Note that more and more revolts began in those areas as time went on (most successfully with Constantine the Great). Climate change clearly spurred on the unstoppable migratory patterns from the coldness of the steppes that had the most noticeable and dynamic impact on Roman social infrastructure.

The changing climate had a variety of negative effects and seems the most obvious watershed between classical civilization and the Middle Ages. However, I am not going to try and solve that ancient historical question here. The migrations happened, and they led to Rome's and Constantinople's downfall. The factors underlying the migrations are irrelevant to our analysis here.

The bottom line is that both the Roman and Byzantine empires found themselves confronted with an irresistible force, and they turned out not to be immovable objects. You can try to stand on the beach and sweep back the tide with a broom, but you are doomed to failure.

|

| Andronicus III and his wife, Anna of Savoy. Andronicus III engaged in civil wars during the 14th Century, and Anna pawned the Byzantine crown jewels to Venice in 1343 to finance her own civil war (Wurttemberg State Library). |

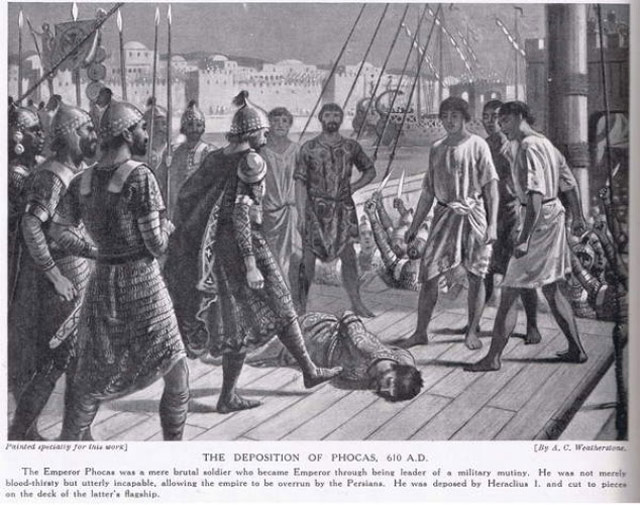

Rome Never Solved Its Succession Problem, Leading to Coups and Endless Civil Wars

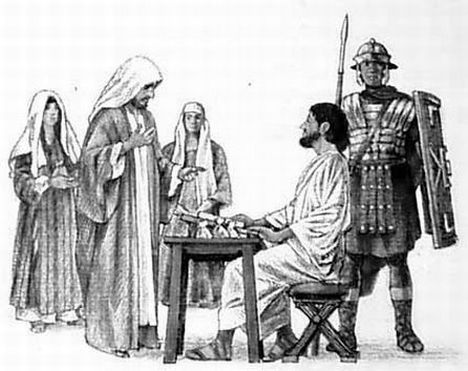

When you read through Gibbon's history of Rome and consult other sources, you quickly realize that there were an awful lot of civil wars in Roman history. One after another, somewhere there was always a general or a wealthy landowner who figured he (or sometimes she) could run things better than the existing government or was entitled to succeed a deceased emperor. There were various causes for these wars, but one enduring problem led to the worst of them: royal succession.

Civil wars and coups began early in Rome's history and never stopped. Caesar and Pompey, Brutus and Marc Antony, Praetorians deciding the next emperor supposedly by rolling dice, one Byzantine general killing another in his bed - there was just one conflict after another related to succession.

The Romans tried various formulations to solve this. The most successful was the system of "adoption" during the Second Century. In this formulation, one emperor "adopted" someone worthwhile. Everyone who mattered accepted the adoptee as the lawful successor and things proceeded smoothly thereafter. This led to a century of peace, the high tide of Roman culture.

This system broke down, however, as generals remembered they could use their military forces to make themselves emperor rather than just accepting the current emperor's choice. This factor is interwined with the migratory patterns discussed above and the changing nature of Rome's enemies because larger and larger garrisons had to be maintained far from the central government. This gave remote generals a ready power base, such as Constantine the Great in the British Isles. Civil wars contributed greatly to the crisis of the Third Century. The same type of thinking led directly to the collapse of the Western Empire in the Fifth Century with the assassination in 461 of the last "good" emperor, Majorian, in a classic power grab.

The Byzantines ultimately settled on hereditary succession, and to some extent, this worked out better than the chaotic classical solution. The downside was that this resulted in a lot of very incompetent emperors (such as Andronicus II), as opposed to in Rome where the winners were usually competent generals. It's difficult to judge which system was more devastating to the sustainability of the empire, but at least incompetent Byzantine emperors didn't lay waste to valuable economic regions.

The Byzantines ultimately settled on hereditary succession, and to some extent, this worked out better than the chaotic classical solution. The downside was that this resulted in a lot of very incompetent emperors (such as Andronicus II), as opposed to in Rome where the winners were usually competent generals. It's difficult to judge which system was more devastating to the sustainability of the empire, but at least incompetent Byzantine emperors didn't lay waste to valuable economic regions.

However, civil wars continued long past the time when the empire could survive them. These included the battles waged by Andronicus III in the 1300s as he tired of waiting for his ineffective father to die. These civil wars sapped the Empire of much-needed strength at critical points when it needed to focus on rebuilding rather than infighting. The coup against Majorian, for instance, basically sealed the Western Empire's fate. One can easily theorize a vastly different outcome of the Empire without the constant self-destruction caused by succession issues.

Romans Stopped Innovating

Of all the reasons for the fall of the Roman Empire, failure to continue innovating is the least obvious but most pernicious. Very few historians put this on their lists, but it absolutely was a top reason for the decline and fall of Roman civilization. Put simply, the Roman Empire stopped moving forward and became a retrograde civilization.

Nobody can deny Roman engineering advances. They built aqueducts, laid down permanent roads throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, invented concrete, and perfected architectural techniques that culminated in the magnificent Haghia Sophia. Their achievements were stunning and can still be seen all across the Roman sphere of influence. But just because progress is made at one point during a civilization does not mean that it continues. Curiously, Roman technical advances simply stopped and actually in some ways reversed themselves.

I can easily make the case that world civilization as a whole was in a retrograde phase up until the rise of the Roman Empire. The Chinese Empire, for instance, became inward-looking and non-expansionary. The heights of western civilization achieved during the ancient Egyptian Empire were followed by the Bronze Age collapse. If you look for great, enduring achievements between the building of the pyramids and the great Greek revival, you aren't going to find much. There was no hint of a cultural resurgence at least until the Greek and Roman civilizations hit their strides 2000 years after the Pyramids were built (and perhaps it was much more than 2000 years depending on how you view certain evidence about the Pyramids' history).

Once the Roman Empire had conquered its main enemies, it also became inward-looking. Basically, Rome became satisfied with what it had and "sat back on its laurels." Gibbon calls it decadence, but that is a misleading characterization that casts moral blame in the wrong direction. It was more like senility, though they both would have had the same result. Instead of the pursuit of pleasure at the expense of industry, the growing sickness in Roman civilization was a sort of oppressive lethargy, perhaps complacency, perhaps dissatisfaction due to constant taxes and a constantly diminishing future, perhaps partly due to not making education more of a priority. The synapses stopped functioning as they had when Caesar took his legions across the English Channel in an audacious gambit that astonished his contemporaries.

I'm going to wrench a comparison way out of context here because it may help you understand my point. In mid-1944, the German line in the USSR had been pushed back in the south but the front further north was still exactly where it had been in late 1941. An oppressive complacency settled over the German high command. They decided - without regard to what was actually happening on the Soviet side - that the next attack would come in the south because, well, it just had to. They wouldn't even consider that it might be a massive thrust in the center toward Minsk because such a thing was inconceivable. It was almost as though they could not force their brains to function any longer to recognize the real threat. The Red Army then struck with savage fury and success precisely where the Germans projected it could never happen. The years of war had dulled their minds to the possibilities and they marched to their doom with blinders on.

The Byzantines stopped thinking just like that. Their old customs were comfortable and they had to be followed to the letter until the end. And, the end came a lot quicker for them precisely because of their slavish devotion to what they thought was their only way of living - following the ways of the glorious past.

While there was heavy Roman trade with India and other Asian areas, there was a lack of exploration for exploration's sake. Basic science that had characterized Greek civilization was minimized. Rome was more interested in amassing wealth through trade and conquest than in innovating and expanding its economic possibilities through inventions and scientific advancements. Roman academics stopped making technical advances that could contribute to its survival and prosperity. The armies were still using the same old roads built during the Republic during the Empire's final days, shipbuilding stagnated, Rome's unique and efficient military equipment more and more began to resemble that of the uneducated barbarians. Progress just stopped.

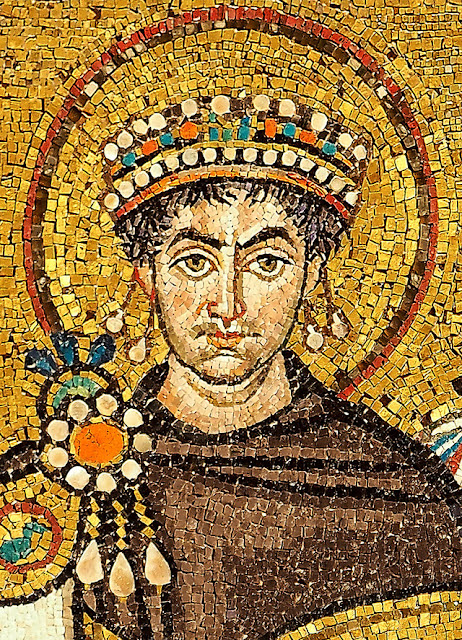

The Byzantine civilization increasingly showed the same retrograde tendencies as the centuries rolled by. It experienced a brief cultural resurgence during the age of Justinian, who was profoundly hated by the people because he did the things that a growing empire required. He taxed people and businesses heavily, he gave them few comforts, he kept his eye on far-flung affairs rather than improving the lot of ordinary citizens. Justinian's focus was on the future, but his (Roman, or more accurately Roman descendants) citizens had had enough of the government's grandiose plans. While Justinian's reign accomplished great and enduring feats of architecture and culture in general, its achievements could not last because the Roman system did not foster continuing creativity.

There was one last brief cultural resurgence in the 1300s, and one can still see some of the traces of this final flowering of culture in Istanbul churches. However, even this focused on impractical things like church construction and artistic achievements. New weapons? New, effective military tactics? Not a hint of them. A growing obsession with religion, exemplified by Andronicus II consulting with astrologers before making his decisions, sapped brainpower that could have been used to figure out ways to restore the Empire.

The Byzantines were still following the old Roman military playbook in the 11th Century. This featured huge armies marching in long columns under crusading warlords. But the world had changed. The old tactics led directly to the disaster at Manzikert because Byzantine enemies were not standing still. The Seljuks and later Turks even used some of the old Roman tactics, such as forming a crescent defensive line, to entrap the Byzantine formations. Classical Romans had used these tactics successfully, but the Byzantines adopted the old Roman forms without understanding the substance that led to victory. The Byzantines simply fell into the same traps that Roman enemies once did because Byzantine society was in a retrograde phase where old lessons were forgotten.

European visitors to the Byzantine court remarked on the wondrous mechanical creations that they observed in the Eastern Emperor's palace ca. 800-900 A.D. This was during a time when their own countries were in a retrograde phase following the collapse of the Western Empire. Most famous of all, the Byzantines developed the famous Greek Fire that won them many critical sea battles. There were mechanical birds that chirped and jumped around, a throne that ascended to the ceiling - these were marvels of the day. Perhaps they were remnants from antiquity, but there is no record of them in the classical records so it appears that Byzantium did have a period of creativity.

Unfortunately, the Byzantines at some undetermined point stopped moving forward just as the earlier Romans in the Western Empire (broadly speaking) had. Basil II, who reigned ca. 1000 A.D., is often cited as the best Byzantine Emperor. However, his achievements were solely military. There was no technological innovation, no great buildings were built, no great works of art created. Aside from military advances, the reign of Basil II was as barren as any other during the Eastern Empire.

A symptom of this stagnation was the Byzantines' enduring commitment to being "Roman" right up until the end. They could never admit nor accept that they had formed a new civilization that had to develop in its own new direction, which was obvious to everyone but themselves. They honored the past at the expense of the future. The technical advances that characterized their early years, such as the aforementioned Greek fire, stopped and were sometimes even forgotten for unknown reasons.

And that is one of the odder and more telling aspects of Byzantine civilization. The late Byzantine courtiers arrived at the point where they did not even understand the purpose of court formalities established centuries earlier (and Byzantium had a lot of court formalities). The Byzantines followed the form and not the substance because the inspiration that generated the substance had been forgotten over the endless centuries. The old forms were followed anyway because nobody any longer had the inspiration to create new forms and "we're Romans, this is what we do, this is our heritage, this is what sets us apart." there was no thought of establishing new norms, a more modern government, an economy based on science and new technology. This is a classic sign of a retrograde civilization.

Here's the clearest example. Byzantine emperors were considered the supreme authority on earth, just as the Constantinople Patriarch was considered the highest religious authority. These forms could not be deviated from without calling into question the entire foundation of the Byzantine state, its purpose and function on earth. Even as the empire shrank to the walls of Constantinople itself and the cemeteries just outside the walls, these fictions and beliefs were followed, much to the amusement and bemusement of outsiders, because there was nothing else to be done. There was no alternative, the state had been put on cruise control a thousand years earlier and the controlling mechanism was broken.

There's a story that may be apocryphal that a bunch of Hollywood old-timers was playing poker one night when the subject turned to what they wished they still had from their youths. There were various answers along the lines of strength, love, health, and so forth. The last to answer was director John Huston, who simply frowned and said, "I wish I still cared." And that was the disease that afflicted late Roman and Byzantine society. Society was not moving forward, everyone could see it, the future was limited and increasingly bleak, and the mass of people simply stopped caring any longer.

That was the "decadence" Gibbon was groping toward but couldn't quite see. The power and dynamism left the Roman culture. It wasn't so much a moral failing as a rational conclusion drawn by many, many people independently that it was now "every man for himself" and thus abstractions like patriotism and self-sacrifice for the good of the state were obsolete. Gibbon was right, but it was not moral weakness or gluttony that led to the collapse in first the West and then the East. It was a rational response to a dying, outmoded system.

The stagnant, obsolete Roman model survived throughout the Middle Ages through a combination of luck, national pride, heroic efforts by unknown warriors, clever (at times) leadership, brutality, political double-dealing, and fortunate location. Its initial enemies such as the Sassanids were similar derelict remnants of the past and could be overcome because they were in even worse shape. Once Byzantium came to grips with rising, dynamic, energetic powers such as the Seljuks and then the Ottomans, however, it had more than met its match. It lost one region, then another, then another, occasionally counterattacking but always on the strategic defensive.

And so, the Empire stumbled along, relying on the brilliant investments of the past such as the sturdy (and thousand-year-old) walls of Constantinople. Byzantium lasted far longer than it should have. The old methods did work, they just were gradually superseded by newer and better systems.

It may seem confusing to ascribe the same causes of decline first to the Western Empire and then the Eastern Empire because the respective downfalls were so widely separated in time. If they used the same system and it was flawed, why did the problems not afflict both at the same time ca 500 A.D.? Why did the Byzantine half of the Empire last for another thousand years?

The key is to understanding (which the Byzantines themselves were unable to do) is that the Eastern Empire was a new civilization that went through roughly the same life cycle as its predecessor. The age of Justinian was like the earlier age of Augustus, for instance, and the reign of Basil II was comparable to that of Constantine the Great. They bookended the greatness of Byzantium. Basil II was the last gasp of dignity and his gallant attempt to reverse the tide only failed because - you guessed it - his terrible successors almost immediately squandered all the resources built up over the preceding thousand years.

Compare Rome and Constantinople to offspring that have the same inherent affliction as their parents. It only manifests itself late in life, perhaps when people are in their 50s or 60s. The inherent defects gradually took down Byzantium just as they had Rome. The last vestiges of the inner mojo was gone by the time of Honorius in the West and Andronicus II in the East (likely much earlier than that in each case, but it was absolutely and completely gone by then). The respective empires could not be rejuvenated any more than today someone with Parkinson's can be completely cured. It is in the bones, in the blood, in the muscles and arteries. The inner disease lingered and manifested itself subtly and gradually, with good days and bad. Finally, it kills you, and death is almost a welcome release from the unceasing torment.

There may be a lesson in there for the present day, both for national and local governments.

If a society is not moving forward, it is moving backward. This sad tendency displayed itself throughout the two phases of Roman civilization, namely, during the classical era and the Byzantine epoch. While completely overlooked by most students of history, it was probably the most important cause of the decline of Roman society.

|

| The Fall of Constantinople, 1453. Failure to handle the issues listed above led to this. |

Conclusion

There are many lists of the reasons for the fall of the Roman Empire. Generally, they include things like invasions and civil wars, and these certainly contributed to the decline. This topic has been the life's work of famous historians such as Edward Gibbon but there is no consensus. It is a great topic because there will never be definite answers, just hypotheses that can never be proven or disproven.

What I have done here is set forth a series of fundamental problems that Roman civilization faced but could not surmount. Migratory patterns, civil wars due to lack of clear rules of succession, the changing nature of enemies, economic collapse, and a growing inability to innovate and move forward. These are all issues we can appreciate today.

Whether one of these factors was more important than another is beside the point. They all contributed to the collapse of the Roman Empire because they lay at the heat of the Roman and Byzantine systems. Solving any one of them would not have been enough, though solving any of them certainly would have helped matters substantially. Given all the handicaps it faced and internal inefficiencies, the wonder is not that the Roman Empire fell when it did, but that it lasted as long as it did.